If robots are really to help us out around the house or care for our injured and elderly, they’re going to want two hands… at least. But using two hands is harder than we make it look — so this robotic control system learns from humans before attempting to do the same.

The idea behind the research, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, isn’t to build a two-handed robot from scratch, but simply to create a system that understands and executes the same type of manipulations that we humans do without thinking about them.

For instance, when you need to open a jar, you grip it with one hand and move it into position, then tighten that grip as the other hand takes hold of the lid and twists or pops it off. There’s so much going on in this elementary two-handed action that it would be hopeless to ask a robot to do it autonomously right now. But that robot could still have a general idea of why this type of manipulation is done on this occasion, and do what it can to pursue it.

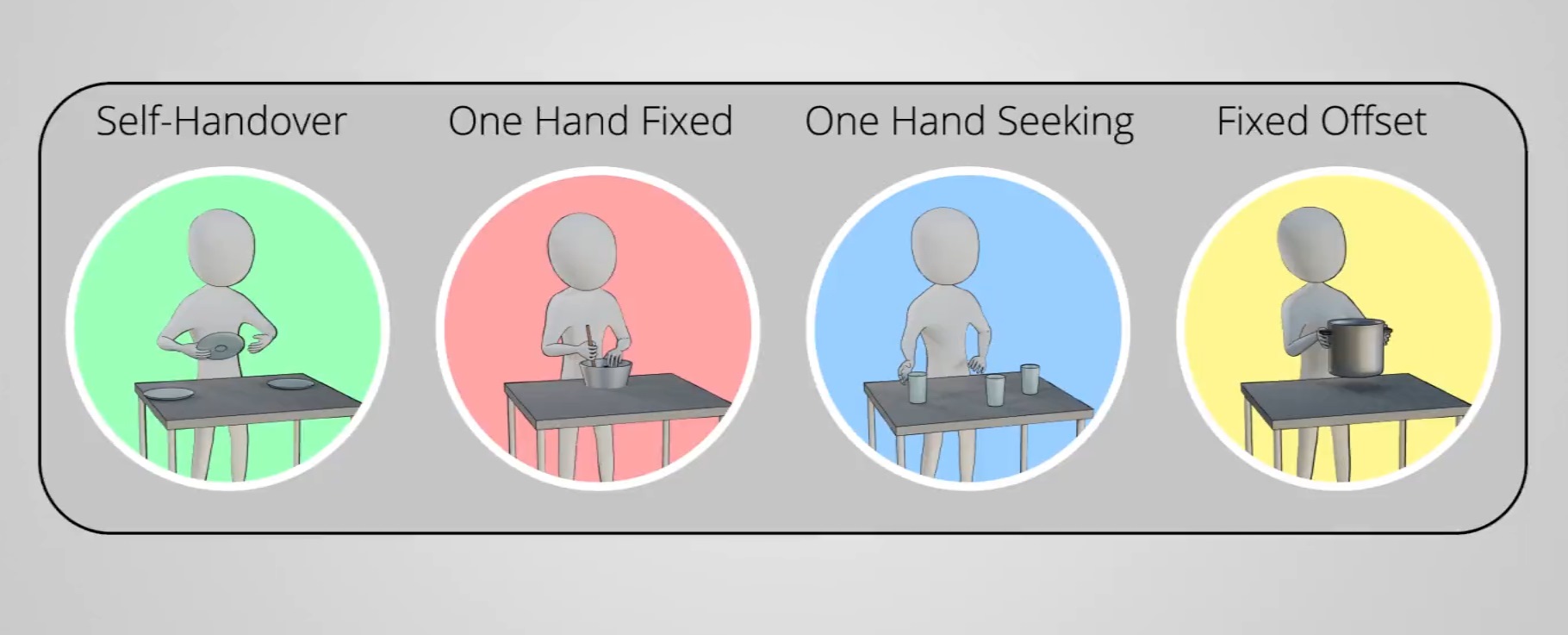

The researchers first had humans wearing a motion capture equipment perform a variety of simulated everyday tasks, like stacking cups, opening containers and pouring out the contents, and picking up items with other things balanced on top. All this data — where the hands go, how they interact, and so on — was chewed up and ruminated on by a machine learning system, which found that people tended to do one of four things with their hands:

- Self-handover: This is where you pick up an object and put it in the other hand so it’s easier to put it where it’s going, or to free up the first hand to do something else.

- One hand fixed: An object is held steady by one hand providing a strong, rigid grip, while the other performs an operation on it like removing a lid or stirring the contents.

- Fixed offset: Both hands work together to pick something up and rotate or move it.

- One hand seeking: Not actually a two-handed action, but the principle of deliberately keeping one hand out of action while the other finds the object required or performs its own task.

The robot put this knowledge to work not in doing the actions itself — again, these are extremely complex motions that current AIs are incapable of executing — but in its interpretations of movements made by a human controller.

You would think that when a person is remotely controlling a robot, it would just mirror the person’s movements exactly. And in the tests, the robot does so to provide a baseline of how without knowledge about these “bimanual actions,” many of them are simply impossible.

You would think that when a person is remotely controlling a robot, it would just mirror the person’s movements exactly. And in the tests, the robot does so to provide a baseline of how without knowledge about these “bimanual actions,” many of them are simply impossible.

Think of the jar-opening example. We know that when we’re opening the jar, we have to hold one side steady with a stronger grip and may even have to push back with the jar hand against the movement of the opening hand. If you tried to do this remotely with robotic arms, that information is not present any more, and the one hand will likely knock the jar out of the grip of the other, or fail to grip it properly because the other isn’t helping out.

The system created by the researchers recognizes when one of the four actions above is happening, and takes measures to make sure that they’re a success. That means, for instance, being aware of the pressures exerted on each arm by the other when they pick up a bucket together. Or providing extra rigidity to the arm holding an object while the other interacts with the lid. Even when only one hand is being used (“seeking”), the system knows that it can deprioritize the movements of the unused hand and dedicate more resources (be it body movements or computational power) to the working hand.

In videos of demonstrations, it seems clear that this knowledge greatly improves the success rate of the attempts by remote operators to perform a set of tasks meant to simulate preparing a breakfast: cracking (fake) eggs, stirring and shifting things, picking up a tray with glasses on it and keeping it level.

Of course this is all still being done by a human, more or less — but the human’s actions are being augmented and re-interpreted into something more than simple mechanical reproduction.

Doing these tasks autonomously is a long ways off, but research like this forms the foundation for that work. Before a robot can attempt to move like a human, it has to understand not just how humans move, but why they do certain things in certain circumstances, and furthermore what important processes may be hidden from obvious observation — things like planning the hand’s route, choosing a grip location, and so on.

The Madison team was led by Daniel Rakita; their paper describing the system is published in the journal Science Robotics.