A voter contact and canvassing company, used exclusively by Republican political campaigns, mistakenly left an unprotected copy of its app’s code on its website for anyone to find.

The company, Campaign Sidekick, helps Republican campaigns canvass their districts using its iOS and Android apps, which pull in names and addresses from voter registration rolls. Campaign Sidekick says it has helped campaigns in Arizona, Montana, and Ohio — and contributed to the Brian Kemp campaign, which saw him narrowly win against Democratic rival Stacey Abrams in the Georgia gubernatorial campaign in 2018.

For the past two decades, political campaigns have ramped up their use of data to identify swing voters. This growing political data business has opened up a whole economy of startups and tech companies using data to help campaigns better understand their electorate. But that has led to voter records spilling out of unprotected servers and other privacy-related controversies — like the case of Cambridge Analytica obtaining private data from social media sites.

Chris Vickery, director of cyber risk research at security firm UpGuard, said he found the cache of Campaign Sidekick’s code by chance.

In his review of the code, Vickery found several instances of credentials and other app-related secrets, he said in a blog post on Monday, which he shared exclusively with TechCrunch. These secrets, such as keys and tokens, can typically be used to gain access to systems or data without a username or password. But Vickery did not test the password as doing so would be unlawful. Vickery also found a sampling of personally identifiable information, he said, amounting to dozens of spreadsheets packed with voter names and addresses.

Fearing the exposed credentials could be abused if accessed by a malicious actor, Vickery informed the company of the issue in mid-February. Campaign Sidekick quickly pulled the exposed cache of code offline.

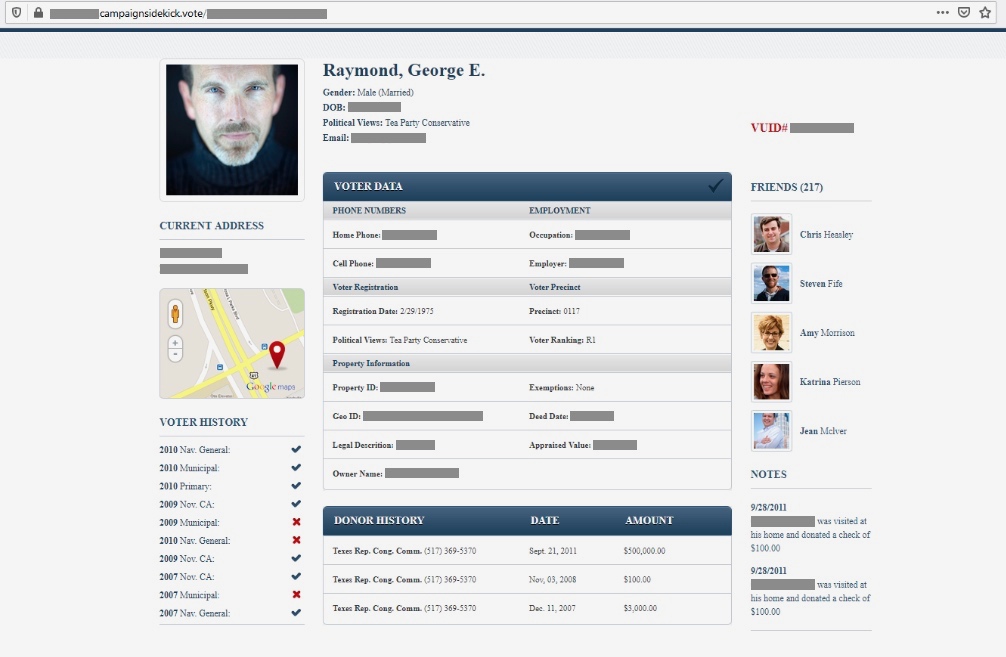

One of the Campaign Sidekick mockups, using dummy data, collates a voter’s data in one place. (Image: supplied)

One of the screenshots provided by Vickery showed a mockup of a voter profile compiled by the app, containing basic information about the voter and their past voting and donor history, which can be obtained from public and voter records. The mockup also lists the voter’s “friends.”

Vickery told TechCrunch he found “clear evidence” that the app’s code was designed to pull in data from its now-defunct Facebook app, which allowed users to sign-in and pull their list of friends — a feature that was supported by Facebook at the time until limits were put on third-party developers’ access to friends’ data.

“There is clear evidence that Campaign Sidekick and related entities had and have used access to Facebook user data and APIs to query that data,” Vickery said.

Drew Ryun, founder of Campaign Sidekick, told TechCrunch that its Facebook project was from eight years prior, that Facebook had since deprecated access to developers, and that the screenshot was a “digital artifact of a mockup.” (TechCrunch confirmed that the data in the mockup did not match public records.)

Ryun said after he learned of the exposed data the company “immediately changed sensitive credentials for our current systems,” but that the credentials in the exposed code could have been used to access its databases storing user and voter data.