In pandemic-free years, America’s biggest trade show, CES, attracts more than 170,000 attendees, bringing traffic that jams surrounding roads day and night. To help absorb at least some of the congestion, the Las Vegas Convention Center (LVCC) last year planned a people-mover to serve an expanded campus. The LVCC wanted transit that could move up to 4,400 attendees every hour between exhibition halls and parking lots.

It considered traditional light rail that could shuttle hundreds of attendees per train, but settled on an underground system from Elon Musk’s The Boring Company (TBC) instead — largely because Musk’s bid was tens of millions of dollars cheaper. The LVCC Loop would transport attendees through two 0.8-mile underground tunnels in Tesla vehicles, four or five at a time.

But planning files reviewed by TechCrunch seem to show that the Loop system will not be able to move anywhere near the number of people LVCC wants, and that TBC agreed to.

Fire regulations peg the occupant capacity in the load and unload zones of one of the Loop’s three stations at just 800 passengers an hour. If the other stations have similar limitations, the system might only be able to transport 1,200 people an hour — around a quarter of its promised capacity.

If TBC misses its performance target by such a margin, Musk’s company will not receive more than $13 million of its construction budget — and will face millions more in penalty charges once the system becomes operational.

Neither TBC nor LVCVA responded to multiple requests for comment.

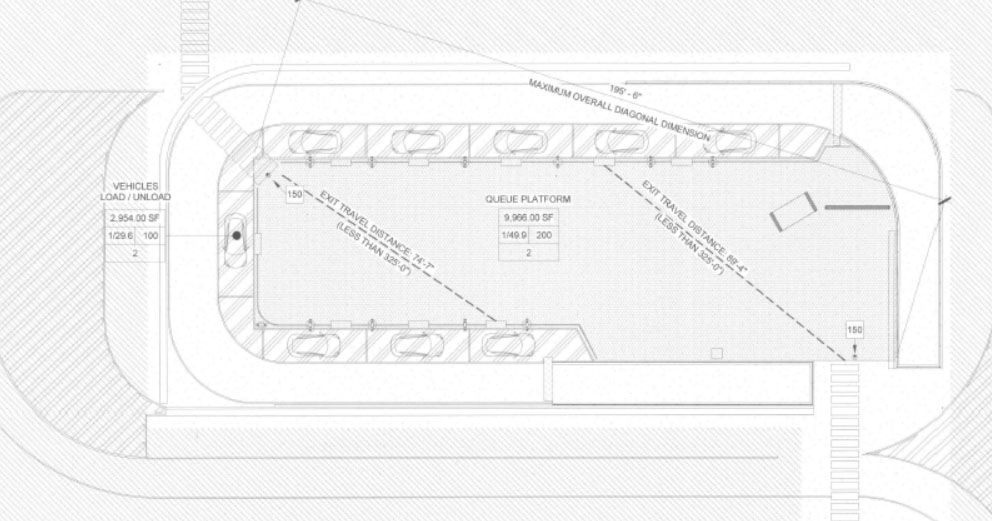

Fire regulations limit the load/unload zone near the cars to 800 people per hour. Credit: TBC/Clark County

The LVCC always realized that it was taking a gamble on the Loop. Although Musk built a short demonstration tunnel near Los Angeles, this would be the first public system with real customers and service requirements. An analysis by Las Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman in May 2019 concluded that TBC’s unproven system presented a high risk for the LVCC’s parent body, the Las Vegas Convention and Visitor’s Authority (LVCVA).

So when the LCVCA wrote its contract with The Boring Company, it did its best to incentivize Musk to deliver on his promises. The contract would be for a fixed price, and TBC would have to hit specific milestones to receive all of its payments. When the bare tunnels are completed, which could happen any day now, TBC will have earned just over 30% of the total. The next big milestone is the completion of the entire working system, which would result in a pay-out of over $10 million.

That was scheduled to have happened by October 1, so that the system would be ready for the next CES show in January. Although CES 2021 has now gone virtual and there is less time pressure on Musk to deliver, he presumably still wants to get paid.

In a tweet this week, Elon Musk wrote that the system would be open in “maybe a month or so. Some finishing touches need to be done on the stations.”

After another milestone for the completion of a test period and safety report, the system’s final three milestones relate to how many passengers it can carry. If the Loop can demonstrate moving 2,200 passengers an hour, TBC will get $4.4 million, then the same payment again for hitting 3,300, and the same again for 4,400 passengers an hour. Together, these capacity payments represent 30% of the fixed price contract.

Even if TBC achieved those numbers during testing, the LVCVA was worried that it might not be able to maintain them once the system was operational, so it inserted yet another requirement: “[TBC] acknowledges liquidated damages are applicable for [TBC’s] failure to provide System Capacity for Full Facility Trade Show Events.”

For each large trade show that TBC fails to transport an average capacity of 3,960 passengers per hour for 13 hours, it will have to pay LVCVA $300,000 in damages. If TBC keeps falling short, it keeps paying, up to a maximum of $4.5 million.

So what is stopping TBC from transporting as many people as both it and the LVCC wants? There are national fire safety rules for underground transit systems that specify alarms, sprinklers, emergency exits and a maximum occupant load, to avoid overcrowding in the event of a fire.

Building plans submitted by The Boring Company include a fire code analysis for one of the Loop’s above-ground stations:

Image source: The Boring Company/Clark County NV

The above screenshot from the plans notes that the area where passengers get into and out of the Tesla cars has a peak occupancy load of 100 people every 7.5 minutes, equivalent to 800 passengers an hour. Even if the other stations had higher limits, this would limit the system’s hourly capacity to about 1,200 people.

“That sounds correct,” says Glenn Corbett, a professor of security, fire and emergency management at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. “But if that’s the bottleneck, the question from a safety standpoint is, what controls that [800 per hour]? Is it just pure honesty and people following the rules, or is there a mechanical thing that keeps them out?”

The plans do not show any turnstiles or barriers to limit entry.

Even without the safety restrictions, the Loop may struggle to hit its capacity goals. Each of the 10 bays at the Loop’s stations must handle hundreds of passengers an hour, corresponding to perhaps 100 or more arrivals and departures, depending on how many people each car is carrying. That leaves little time to load and unload people and luggage, let alone make the 0.8-mile journey and occasionally recharge.

[gallery ids="2061530,2061529,2061685,2061528"]

Although TBC’s Loop website says that the system will use autonomous vehicles, a TBC executive told a planning committee last year that the cars would have human drivers “for additional safety.” TBC had proposed developing a larger capacity autonomous shuttle for the Loop, capable of carrying up to 16 people. The latest plans all show traditional sedans, however, and another Musk tweet this week admitted: “We simplified this a lot. It’s basically just Teslas in tunnels at this point.”

The most recent documents filed by TBC also show changes to the Loop’s original design.

Gone are striking curved roofs, with both aboveground stations now having flat photovoltaic canopies to help charge the Tesla vehicles. These terminal stations each have a single Supercharger station, and a “showpiece sculpture” consisting of a concrete segment similar to those used in the tunnels below.

The central, subterranean station has a large, open platform, and also houses the electrical, fire safety and IT equipment. Each station will have bays for 10 Tesla vehicles to load and unload passengers.

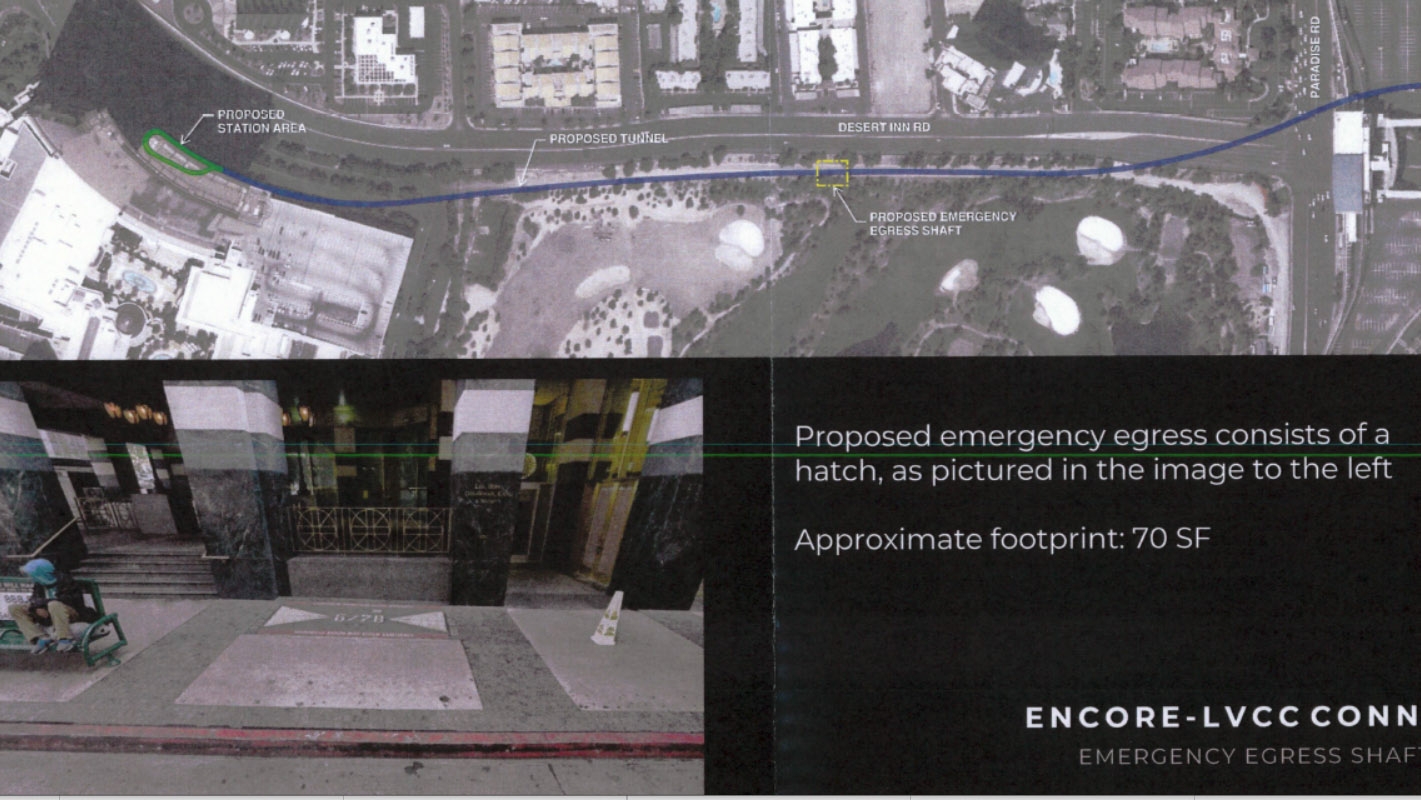

Even before the first Loop is operating, TBC is planning two more Loop tunnels nearby, connecting the LVCC to the Wynn Encore and Resorts World casinos.

The tunnel to the Encore is long enough that safety regulations require an emergency exit about halfway along. Plans indicate an emergency egress shaft and a small hatch, but it is unclear whether passengers escaping a fire or breakdown would be expected to climb stairs or even a ladder.

Loop extension egress. Image source: The Boring Company/Clark County NV

TBC last year suggested an emergency ladder for its proposed Loop between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., a system that Corbett called “the definition of insanity,” as it did not account for passengers with limited mobility. That project is now on pause.

TBC’s stated aim is to expand the LVCC Loop from a local people mover to a Vegas-wide transit system serving the Strip, the airport and eventually extending all the way to Los Angeles. If the company struggles to deliver capacity — and revenue — from its small-scale Convention Center system, the future of those ambitions could be in doubt.