WeChat continues to advance its shopping ambitions as the social networking app turns 10 years old. The Chinese messenger facilitated 1.6 trillion yuan (close to $250 billion) in annual transactions through its “mini programs,” third-party services that run on the super app that allow users to buy clothes, order food, hail taxis and more.

That is double the value of transactions on WeChat’s mini programs in 2019, the networking giant announced at its annual conference for business partners and ecosystem developers, which normally takes place in its home city of Guangzhou in southern China but was moved online this year due to the pandemic.

To compare, e-commerce upstart Pinduoduo, Alibaba’s archrival, saw total transactions of $214.7 billion in the third quarter.

WeChat introduced mini programs in early 2017 in a move some saw as a challenge to Apple’s App Store and has over time shaped the messenger into an online infrastructure that keeps people’s life running. It hasn’t recently disclosed how many third-party lite apps it houses, but by 2018 the number reached one million, half the size of the App Store at the time.

From Tencent’s strategic perspective, the growth in mini program-based transactions helps further the company’s goal to strengthen its fintech business, which counts digital payments as a major revenue driver.

A big proportion of WeChat’s mini programs are games, which the app said exceeded 500 million monthly users thanks to a boost in female and middle-aged users, as well as players residing in China’s Tier 3 cities, WeChat said.

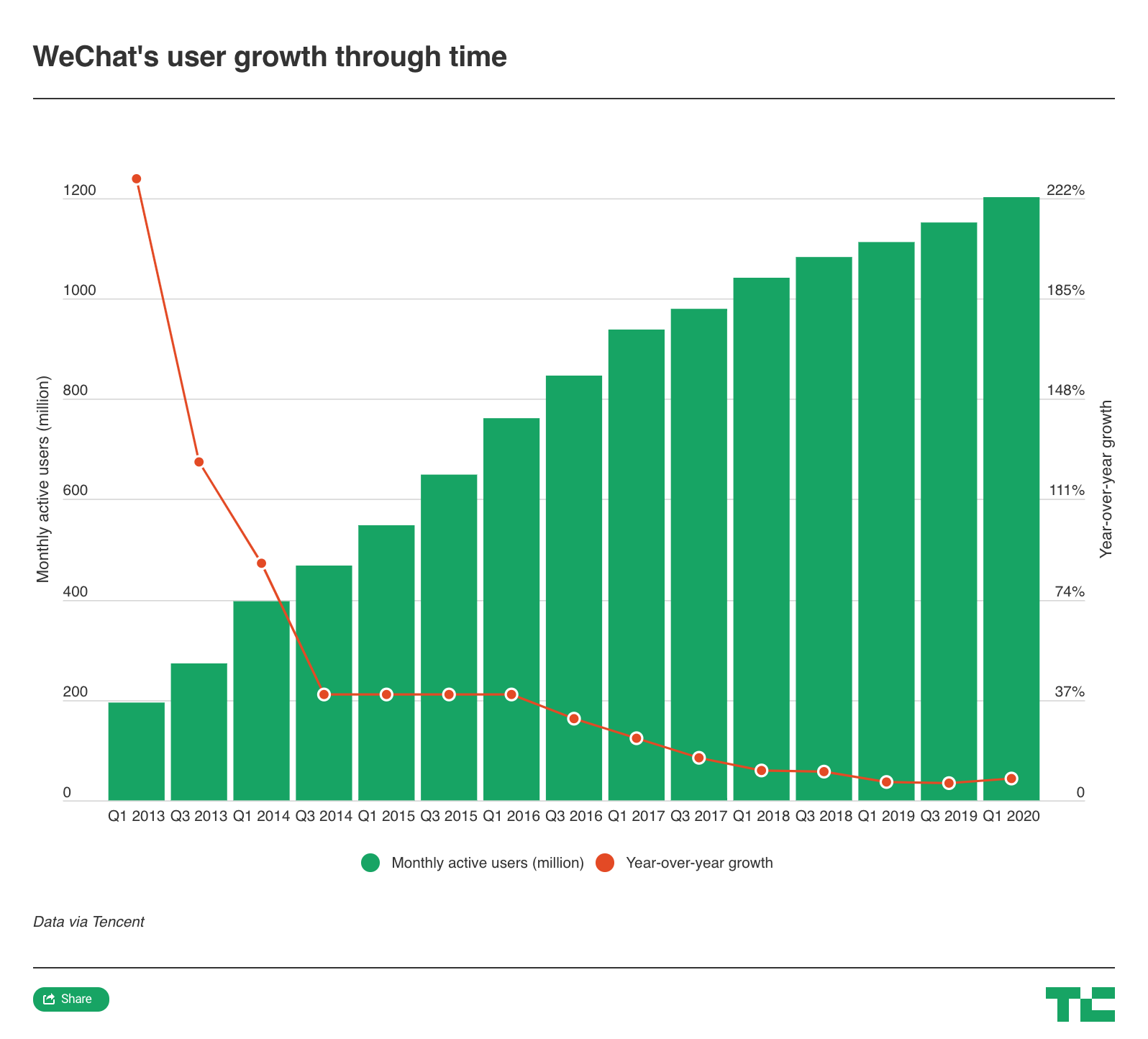

The virtual conference also unveiled a set of other milestones from China’s biggest messaging app, which surpassed 1.2 billion monthly active users last year.

Among its monthly users, 500 million have tried the WeChat Search function. The Chinese internet is carved into several walled gardens controlled by titans like Tencent, Alibaba and ByteDance, which often block competitors from their services. When users search on WeChat, they are in effect retrieving information published on the messenger as well as Tencent’s allies like Sogou, Pinduoduo and Zhihu, rather than the open web.

Among its monthly users, 500 million have tried the WeChat Search function. The Chinese internet is carved into several walled gardens controlled by titans like Tencent, Alibaba and ByteDance, which often block competitors from their services. When users search on WeChat, they are in effect retrieving information published on the messenger as well as Tencent’s allies like Sogou, Pinduoduo and Zhihu, rather than the open web.

WeChat said 240 million people have used its “payments score.” When the feature debuted back in 2019, there was speculation that it signaled WeChat’s entry into consumer credit finance and participation in the government’s social credit system. WeChat reiterated at this year’s event that the WeChat score does neither of that.

Like Ant’s Sesame Score, the rating system works more like a royalty program, “designed to build trust between merchants and users.” For instance, people who reach a certain score can waive deposits or delay payments when using merchant services on WeChat. The score, WeChat said, helped users save more than $30 billion in deposits a year.

WeChat’s enterprise version has surpassed 130 million active users. Its biggest rival, Dingtalk, operated by Alibaba, reached 155 million daily active users last March.

The one-day event concluded with the much-anticipated appearance of Allen Zhang, WeChat’s creator. Zhang went to great lengths to talk about WeChat’s nascent short-video feature, which is somewhat similar to Snap’s Stories. He didn’t disclose the performance of short videos because “the PR team doesn’t allow” him to, but said that “if we set a goal for ourselves, we will have to achieve it.”

Zhang also announced the WeChat team is weighing up an input tool for users. It’d be a tiny project given Tencent’s colossal size, but the project reflects Zhang’s belief in “privacy protection,” despite public skepticism about how WeChat handles user data.

“If we analyze [users’ chat history], we can bring great advertising revenue to the company. But we don’t do that, so WeChat cares a lot about user privacy,” asserted Zhang.

“But why do you still get ads [related to] what you have just said on WeChat? There are many other channels that process your information, not just WeChat. From there, our technical team said, ‘Why don’t we create an input tool ourselves?'”