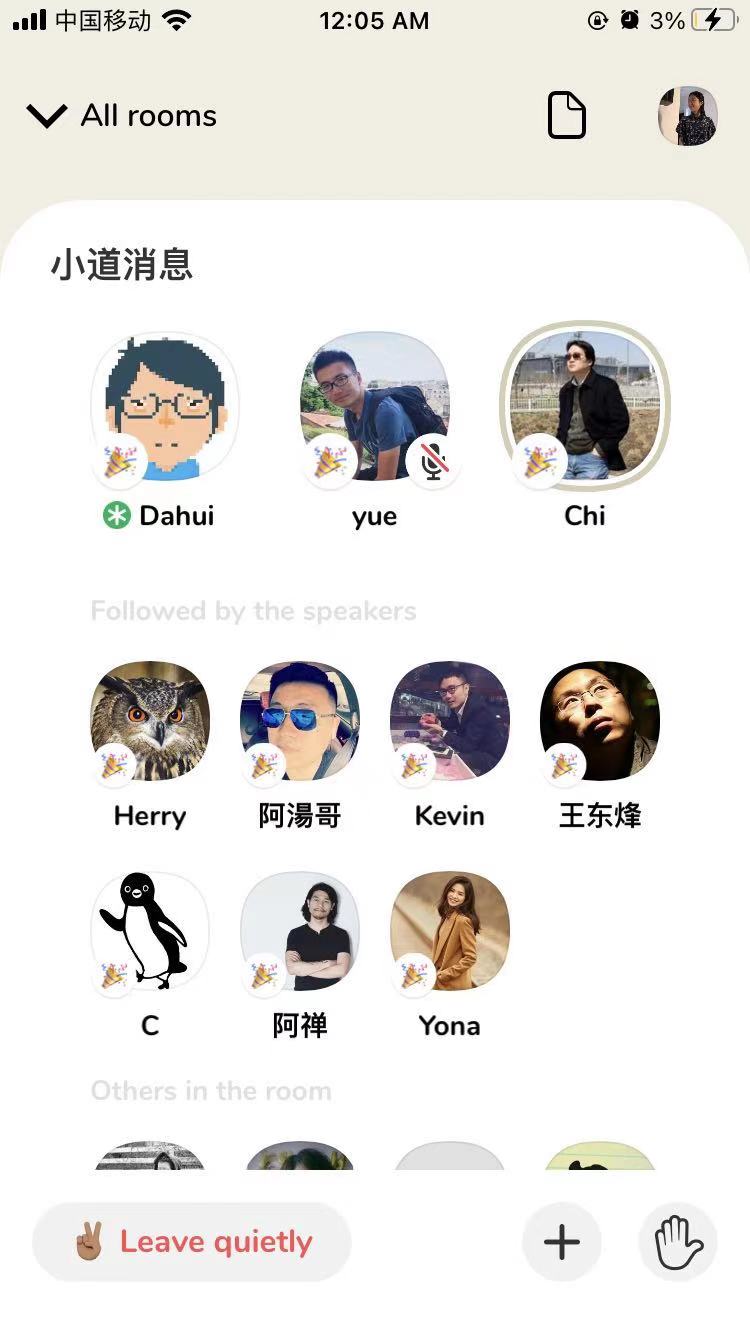

On Friday just past midnight, I stumbled across a Clubhouse room hosted by a well-known figure in the Chinese startup community, Feng Dahui. At half-past midnight, the room still had nearly 500 listeners, many of whom were engineers, product managers, and entrepreneurs from China.

The discussion centered around whether Clubhouse, an app that lets people join pop-up voice chats in virtual rooms, will succeed in China. That’s a question I have been asking myself in recent weeks. Given the current hype swirling in Silicon Valley about the audio social network, it’s unsurprising to see well-informed, tech-savvy Chinese users start flocking to the platform. Demand for invitations in China runs high, with people paying as much as $100 to buy one from scalpers.

Many users I talked to believe the app won’t reach its full potential or even just find product-market fit in China before it gets banned. Indeed, a handful of well-attended Chinese-language rooms touch on topics that are normally censored in China, from crypto trading to protests in Hong Kong.

If it’s of any consolation, Clubhouse clones and derivatives are already in the making in China. A Chinese entrepreneur and blogger who goes by the nickname Herock told me he is aware of at least “dozens of local teams” that are working on something similar. Moreover, voice-based networking has been around in China for years, albeit in different forms. If Clubhouse is blocked, will any of its alternatives go on to succeed?

Information control

A direct Clubhouse clone probably won’t work in China.

A few factors dim its prospects in the country, which has nearly one billion internet users. The major appeal of Clubhouse is the organic flow of conversations in real time. But “how could the Chinese government allow free-flowing discussions to happen and spread without control,” a founder of a Chinese audio app rhetorically asked, declining to be named for this story. Video live streaming in China, for example, is under close regulatory oversight limiting who can speak and what they can say.

The founder then cited a famous online protest back in 2011. Thousands of small vendors launched a cyber attack on Alibaba’s online mall over a proposed fee hike. The tool they used to coordinate with one another was YY, which started out as a voice-based chatting software for gamers and later became known for video live streaming.

“The authorities dread the power of real-time audio communication,” the founder added.

There are signs that Clubhouse may already be the target of censorship. While Clubhouse works perfectly in China without the need for a virtual private network (VPN) or other censorship-circumvention tools (at least for the moment), the iOS-exclusive app is unavailable on China’s App Store. Clubhouse was removed there shortly after its global release in late September, app analytics firm Sensor Tower said.

Currently, in order to install Clubhouse, Chinese users need to install the app by switching to an App Store located in another country, which further limits the product’s reach to users who have the means of using a non-local store.

It’s unclear whether Apple preemptively delisted Clubhouse in anticipation of government action, given that any later removal of a major foreign app in China could stir up accusations of censorship. Alternatively, Clubhouse might have voluntarily pulled the app itself knowing that any form of real-time broadcasting won’t go unchecked by Chinese regulators, which would inevitably compromise user experience.

Entering China could be way down on Clubhouse’s to-do list given the traction it is gaining elsewhere. The app has seen about 3.6 million worldwide installs so far, according to Sensor Tower estimates. The majority of its lifetime installs originate in the United States, where the app has seen nearly 2 million first-time downloads, followed by Japan and Germany both with over 400,000 downloads.

Clubhouse elites

Clubhouse room hosted by Feng Dahui, a respected figure in China’s startup world. (Screenshot by TechCrunch)

The improbability of uncensored and open discussions on the Chinese internet may explain why the market hasn’t seen its own Clubhouse. But even if an app like Clubhouse is allowed to exist in China, it may not reach the same massive scale across the country as Douyin (TikTok’s Chinese version) and WeChat did.

The app is “elitist,” sort of like a voice version of Twitter, said Marco Lai, CEO and founder of Lizhi, a NASDAQ-listed Chinese audio platform. So far, Clubhouse’s invite-only model has confined its American user base largely to the tech, arts and celebrity circles. Herock observed that its Chinese demographics mirror the trend, with users concentrated in fields like finance, startup and product management, as well as crypto traders.

Even among these users though, there is the question of free time. The other night, I was up at midnight eavesdropping on a group of ByteDance employees. In fact, I’ve mostly been on Clubhouse in the late evenings after work, because that’s when user activity in China appears to peak. “Who in China has that much time?” said Zhou Lingyu, founder of Rainmaker, a Chinese networking community for professionals, when I asked whether she thinks Clubhouse will attract the masses in China.

While her remark may not apply to everyone, the tech-centric, educated crowds in China — the demographic that Clubhouse appears to be targeting or at least attracting — are also those most likely to work the notorious “996” schedule, the long hours practice common in Chinese tech companies. The type of “meaningful conversations” that Clubhouse encourages is desirable, but the app’s real-time, spontaneous nature is also a lot to ask of 996 workers, who likely prefer more efficient and manageable use of time.

Moderators may also need material incentives to remain active aside from the pure passion in connecting with other human beings. One potential solution is to turn quality conversations into podcast episodes. “Clubhouse is for one-off, casual conversations. Those who produce high-quality content would want to record the conversation so it could be for repeatable consumption later on,” said Zhou.

Chinese counterparts

In China, audio networking has played out in slightly different shapes. Some companies place a great deal of focus on gamification, filling their apps with playful, interactive features.

Lizhi’s social podcast app, for example, is not just about listening. It also lets listeners message hosts, tip them through virtual gifts, record themselves shadowing a host who is reading a poem, compete in online karaoke contests, and more.

Interaction between hosts and listeners happens in a relatively orchestrated way, as Lizhi’s operational staff design campaigns and work with content creators behind the scenes to ensure content quality and user engagement. Clubhouse growth, in comparison, is more organic.

“The Chinese products focus more on spectatorship and performance, not so much translating natural social behavior in real life into a product. Clubhouse features are simple. It’s more like a coffee shop,” Lai said.

Lizhi’s other voice product Tiya is considered a close answer to Clubhouse, but Tiya’s users are young — the majority of whom are 15-22 years old — and it focuses on entertainment, letting users chat via audio while they play games and watch sports. That also feeds the need for companionship.

Dizhua, which launched in 2019, is another Chinese app that’s been compared to Clubhouse. Unlike Clubhouse, which relies on people’s existing networks for room discovery, Dizhua matches anonymous users based on their declared interests. Clubhouse conversations can start and die off casually. Dizhua encourages users to pick a theme and stay engaged.

“Clubhouse is a pure audio app, with no timeline, no comment, et cetera,” said Armin Li, an expert in residence with a venture capital firm in China. “It’s a kind of casual and drop-in style for the scenarios where user needs are not clear like hangout or multitasking … Its high community participation, content quality, and user quality are unseen in Chinese voice products.”

The bottom line is: The conversations that happen on Chinese platforms are monitored by content auditors. User registration requires real-name verification on internet platforms in China, so there’s no real anonymity online. The topics that users can discuss are limited, often leaning towards the fun and innocuous.

Why do people in China join Clubhouse anyway? Some, like me, joined out of FOMO. Entrepreneurs are always scouring for the next market opportunity, and product managers from internet giants hope to learn a thing or two from Clubhouse that they could apply to their own products. Bitcoin traders and activists, on the other hand, see Clubhouse as a haven outside the purview of Chinese regulators.

Technical support

One thing I find impressive about Clubhouse is how smoothly it works in China. Even when a foreign app isn’t banned in China, it often loads slowly due to its servers’ distance from China.

Clubhouse doesn’t actually build the technology supporting its enormous chat groups that sometimes reach thousands of participants. Instead, it uses a real-time audio SDK from Agora, two sources told me. The South China Morning Post also reported that. When asked to verify the partnership, Agora CEO Tony Zhao said via email he can’t confirm or deny any engagement between his company and Clubhouse.

Rather, he emphasized Agora’s “virtual network,” which overlays on top of the public internet running on more than 200 co-located data centers worldwide. The company then uses algorithms to plan traffic and optimize routing.

Noticeably, Agora’s operations teams are mainly in China and the U.S., a setup that inevitably raises questions about whether Clubhouse data are within the scope of Chinese regulations.

With real-time voice technology providers like Agora, opportunists are able to build Clubhouse clones quickly at low costs, Herock said. Chinese entrepreneurs are unlikely to copy Clubhouse directly due to local regulatory challenges and different user behavior, but they will race to crank out their own interpretations of voice networking before the hype around Clubhouse fades away.