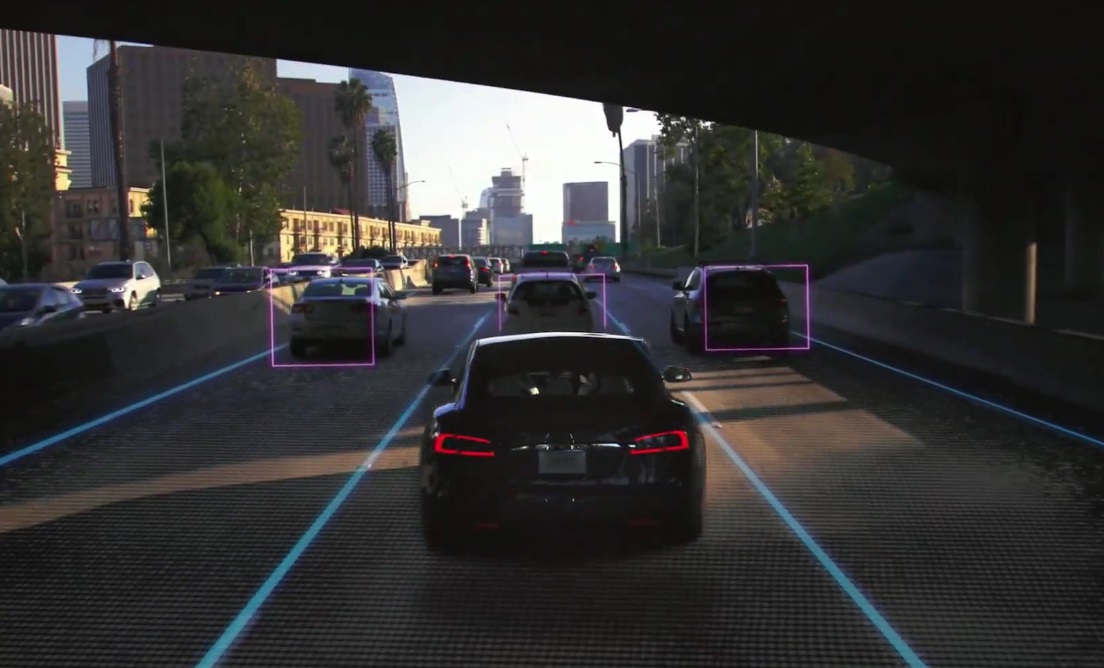

At its “Autonomy Day” today, Tesla detailed the new custom chip that will be running the self-driving software in its vehicles. Elon Musk rather peremptorily called it “the best chip in the world…objectively.” That might be a stretch, but it certainly should get the job done.

Called for now the “full self-driving computer,” or FSD Computer, it is a high-performance, special-purpose chip built (by Samsung, in Texas) solely with autonomy and safety in mind. Whether and how it actually outperforms its competitors is not a simple question and we will have to wait for more data and closer analysis to say more.

Former Apple chip engineer Pete Bannon went over the FSDC’s specs, and while the numbers may be important to software engineers working with the platform, what’s more important at a higher level is meeting various requirements specific to self-driving tasks.

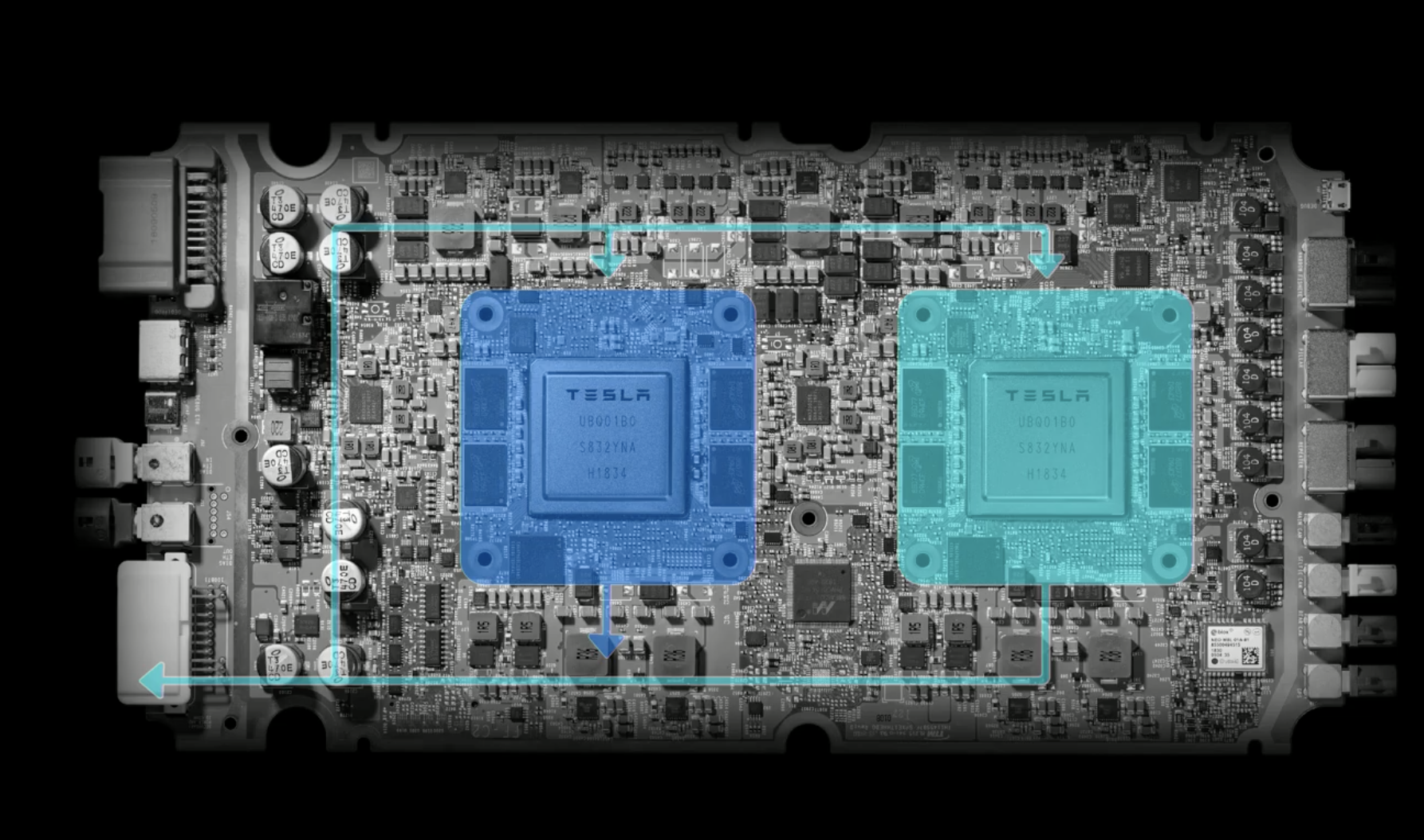

Perhaps the most obvious feature catering to AVs is redundancy. The FSDC consists of two duplicate systems right next to each other on one board. This is a significant choice, though hardly unprecedented, simply because splitting the system in two naturally divides its power as well, so if performance were the only metric (if this was a server, for instance) you’d never do it.

Here, however, redundancy means that should an error or damage creep in somehow or another, it will be isolated to one of the two systems and reconciliation software will detect and flag it. Meanwhile the other chip, on its own power and storage systems, should be unaffected. And if something happens that breaks both at the same time, the system architecture is the least of your worries.

Here, however, redundancy means that should an error or damage creep in somehow or another, it will be isolated to one of the two systems and reconciliation software will detect and flag it. Meanwhile the other chip, on its own power and storage systems, should be unaffected. And if something happens that breaks both at the same time, the system architecture is the least of your worries.

Redundancy is a natural choice for AV systems, but it’s made more palatable by the extreme levels of acceleration and specialization that are possible nowadays for neural network-based computing. A regular general-purpose CPU like you have in your laptop will get schooled by a GPU when it comes to graphics-related calculations, and similarly a special compute unit for neural networks will beat even a GPU. As Bannon notes, the vast majority of calculations are a specific math operation and catering to that yields enormous performance benefits.

Pair that with high speed RAM and storage and you have very little in the way of bottlenecks as far as running the most complex parts of the self-driving systems. The resulting performance is impressive, enough to make a proud Musk chime in during the presentation:

“How could it be that Tesla, who has never designed a chip before, would design the best chip in the world? But that is objectively what has occurred. Not best by a small margin, best by a big margin.”

“How could it be that Tesla, who has never designed a chip before, would design the best chip in the world? But that is objectively what has occurred. Not best by a small margin, best by a big margin.”

Let’s take this with a grain of salt, as surely engineers from Nvidia, Mobileye, and other self-driving concerns would take issue with the statement on some grounds or another. And even if it is the best chip in the world, there will be a better one in a few months — and regardless, hardware is only as good as the software that runs on it. (Fortunately Tesla has some amazing talent on that side as well.)

(One quick note for a piece of terminology you might not be familiar with: OPs. This is short for operations for second, and it’s measured in the billions and trillions these days. FLOPs is another common term, which means floating-point operations per second; these pertain to higher-precision math often used by supercomputers for scientific calculations. One isn’t better or worse than the other, and they shouldn’t be compared directly or considered exchangeable.)

High-performance computing tasks tend to drain the battery, like doing transcoding or HD video editing on your laptop and it bites the dust after 45 minutes. If your car did that you’d be mad, and rightly so. Fortunately a side effect of acceleration tends to be efficiency.

The whole FSDC runs on about 100 watts (or 50 per compute unit), which is pretty low — it’s not cell phone chip low, but it’s well below what a desktop or high performance laptop would pull, less even than many single GPUs. Some AV-oriented chips draw more, some draw less, but Tesla’s claim is that they’re getting more power per watt than the competition. Again, these claims are difficult to vet immediately considering the closed nature of AV hardware development, but it’s clear that Tesla is at least competitive and may very well beat its competitors on some important metrics.

Two more AV-specific features found on the chip, though not in duplicate (the compute pathways converge at some point), are some CPU lockstep work and a security layer. Lockstep means that it is being very carefully enforced that the timing on these chips is the same, ensuring that they are processing the exact same data at the same time. It would be disastrous if they got out of sync either with each other or with other systems. Everything in AVs depends on very precise timing while minimizing delay, so robust lockstep measures are put in place to keep that straight.

Two more AV-specific features found on the chip, though not in duplicate (the compute pathways converge at some point), are some CPU lockstep work and a security layer. Lockstep means that it is being very carefully enforced that the timing on these chips is the same, ensuring that they are processing the exact same data at the same time. It would be disastrous if they got out of sync either with each other or with other systems. Everything in AVs depends on very precise timing while minimizing delay, so robust lockstep measures are put in place to keep that straight.

The security section of the chip vets commands and data cryptographically to watch for, essentially, hacking attempts. Like all AV systems, this is a finely-oiled machine and interference must not be allowed for any reason — lives are on the line. So the security piece watches the input and output data carefully to watch for anything suspicious like spoofed visual data (to trick the car into thinking there’s a pedestrian, for instance) to tweaked output data (say to prevent it from taking proper precautions if it does detect a pedestrian).

The most impressive part of all might be that this whole custom chip is backwards-compatible with existing Teslas, able to be dropped right in, and it won’t even cost that much. Exactly how much the system itself costs Tesla, and how much you’ll be charged as a customer — well, that will probably vary. But despite being the “best chip in the world,” this one is relatively affordable.

Part of that might be from going with a 14nm fabrication process rather than the sub-10nm process others have chosen (and to which Tesla may eventually have to migrate). For power savings the smaller the better and as we’ve established, efficiency is the name of the game here.

We’ll know more once there’s a bit more objective — truly objective, apologies to Musk — testing on this chip and its competition. For now just know that Tesla isn’t slacking and the FSD Computer should be more than enough to keep your Model 3 on the road.